Fetal pioneer Diana Farmer leads innovative research, which holds promise of saving lives and lifetimes.

Post published on FetalHealthFoundation.org with the permission of UC Davis Fetal Care Treatment Center

In the United States each year, between 1,500 and 2,000 babies are born with spina bifida, the most common cause of lifelong childhood paralysis in the United States. The four types of spina bifida range from mild to severe: occulta, closed neural tube defects, meningocele and myelomeningocele.

Spina bifida occurs when the spinal cord improperly forms in utero, leaving a section of neural tube open, exposing tissues and nerves and causing a range of cognitive, mobility, urinary and bowel disabilities. Spina bifida is a lifelong condition involving multiple operations, many hospital stays and, in some cases, lifelong use of a wheelchair.

While surgery performed after birth can help reduce severity of the effects, repair before birth is proven to be a more successful option to avoid or decrease problems for diagnosed infants. That’s because spinal damage worsens during the course of the pregnancy.

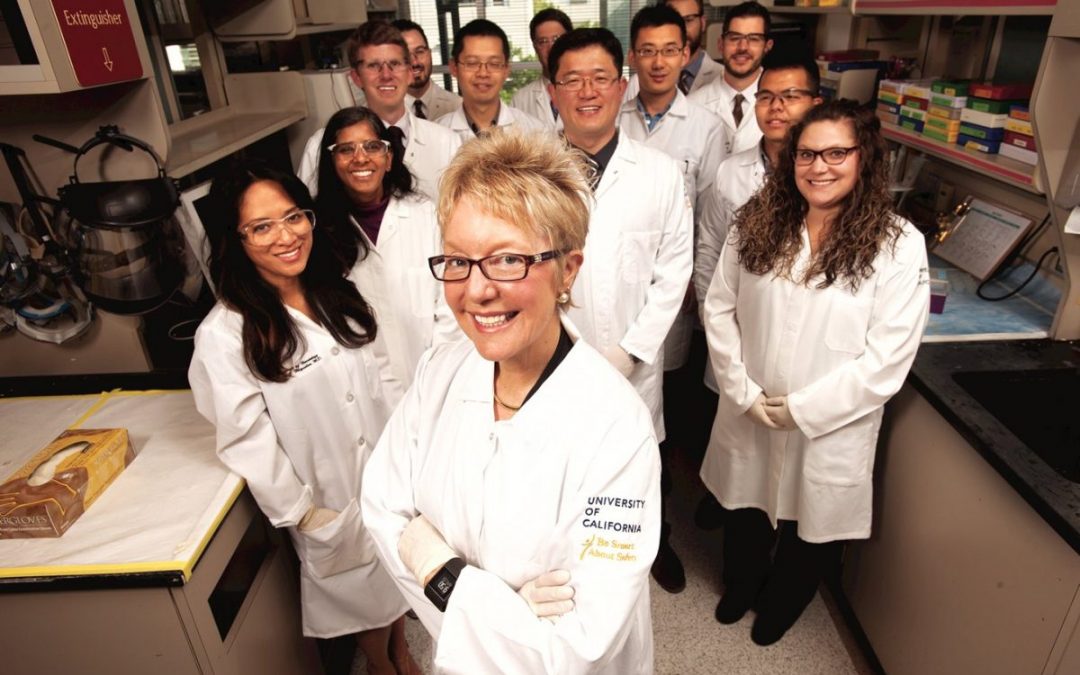

One fetal pioneer, Dr. Diana Farmer, who was the first female fetal surgeon in the world, has been on the forefront of spina bifida research for decades. Her mission? To save lives and lifetimes for patients and families affected by spina bifida.

Her latest research, which involves fetal stem cell therapy, holds the hope of providing what so many families are looking for: a cure. Watch Video

The beginnings of fetal interventions

It has been the lifeblood and mission of Diana Farmer, who is currently chair of surgery and surgeon-in-chief at UC Davis Children’s Hospital, to find a cure for spina bifida.

Growing up in the 1960’s, Farmer’s mother taught Sunday school for disabled children. It was where she first met children who had spina bifida.

“It was a really crummy disease,” Farmer said.

“The main reason kids got an operation after birth was to close the [defect] and prevent meningitis. But nobody thought you’d be making them better, functionally. It just didn’t seem fair.”

Those early days planted a seed, which led Farmer to complete her medical degree at the University of Washington in Seattle and her general residency training at UC San Francisco. Her pediatric surgical training was completed at Children’s Hospital of Michigan.

In 1981, Michael Harrison performed the world’s first open fetal surgery at UC San Francisco. Farmer trained under Harrison and was drawn to the field of fetal surgery because it was something new and exciting.

“We saw it as a way to help some babies we couldn’t help after birth and as pediatric surgeons. That’s what we are put on the planet for: to fix babies,” Farmer said.

MOMS study breaks boundaries

In 2002, Farmer set out to research whether fetal surgery could help patients diagnosed with spina bifida. With funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), researchers performed a randomized trial of myelomeningocele (MMC) closure before and after birth at three medical centers nationally. MMC is the most severe form of spina bifida. The breakthrough study was called the Management of Myelomeningocele Study, or MOMS.

Patients were randomly selected to either receive standard surgery after birth or fetal surgery before birth. In the fetal surgery group, physicians would perform open fetal surgery between 22 and 26 weeks gestation. Although fetal surgery couldn’t restore already lost neurological function, the procedure could prevent additional loss from occurring during the remainder of the pregnancy.

For seven years, this research continued, with evaluations of babies done at 12 and 30 months after birth.

When the research ended, the findings were staggering.

Results showed that surgery prior to birth reduced the need for ventriculo-peritoneal shunting, or a V-P shunt, which treats fluid build-up in the brain called hydrocephalus. In the majority of babies with severe spina bifida, the alteration to the brain’s development causes hydrocephalus, a condition in which excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collects in the brain’s ventricles.

Forty percent of the toddlers in the fetal surgery group needed a shunt, as opposed to 82 percent of the toddlers in the postnatal surgery group.

In addition, intervention before birth reduced the severity of changes in the shape of the skull called the Arnold-Chiari malformation type II. For a quarter of babies who received fetal surgery, the deformity that was detected on ultrasound had reversed or vanished.

The MOMS trial, which concluded in 2011, is the reason why fetal surgery is offered today for spina bifida.

“Before this, everyone thought that spina bifida was a fixed defect – you were just paralyzed for life,” Farmer said. “But I think the most important part that came out of the MOMS trial was that there’s some hope, there’s some plasticity with the spinal cord, and if we intervene early, we can make a difference.”

Mobility still remained an issue. Fifty-eight percent of the children who were treated in utero were unable to walk independently at 30 months of age. There was more work to be done.

Animal research shows promise

In 2013, Farmer embarked upon a new study, this time partnering with UC Davis Surgical Bioengineering Laboratory and co-director Aijun Wang. Together they investigated the power of stem cells in animal models.

Could human placenta-derived stem cells help repair spina bifida before birth and provide significant and consistent improvement in neurologic function at birth in sheep models?

In a word: Yes. Farmer was able to show that prenatal surgery combined with stem cells, preserved in hydrogel and held in place with a cellular scaffold, preserved the ability of lambs born with the disorder to walk without noticeable disability.

Sixty-seven percent of the lambs treated with stem cells were able to walk independently, with two exhibiting no motor deficits whatsoever.

In contrast, none of the lambs treated with the hydrogel and scaffold alone were capable of walking.

In 2017, the research team learned that spina bifida affects bulldogs. In an attempt to help the dogs and to show that stem cells can help in other species, two English bulldog puppies born with spina bifida named Darla and Spanky, were transported from Southern California Bulldog Rescue to the UC Davis William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital. The puppies were 10 weeks old and were unable to walk or wag their tails. They were the first dogs to receive a combination of surgery and canine stem cells, this time after birth.

At their post-surgery appointment at four months old, the puppies showed off their abilities to walk, run and play.

“The initial results of the surgery are promising, as far as hind limb control,” said UC Davis veterinary neurosurgeon Beverly Sturges. “Both dogs seemed to have improved range of motion and control of their limbs.”

The puppies have since been adopted and continue to do well at their home in New Mexico.

Stem cells – the next frontier

In November of 2018, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) awarded a $5.66 million grant to Diana Farmer’s research team to help them expand on the approach that has been successful in animal models.

The grant enables the UC Davis team to perform final testing and preparations needed for FDA approval to start the first human clinical trial using stem cells during open fetal MMC repairs at UC Davis by 2021.

“There were many times of frustration, many times when cell types we explored and worked with didn’t work,” Farmer said.

“But it’s the patients, seeing them, talking to them and working with them, that keeps me motivated to do the science, to keep persevering.”

If the therapy is successful, a long-awaited cure will finally be available for patients like Evie Brave, who just celebrated her first birthday. Her mother Breen Hardin had an open fetal MMC repair in December 2017 at UC Davis.

“The fetal surgery team at UC Davis has been invaluable from day one. They gave us confidence and provided hope during a challenging time,” said Hardin. “I cannot wait to see the advancements that team at UC Davis makes with stem cells. I am hopeful that in the future, children diagnosed with spina bifida will see a cure with stem cells.”

Farmer, Wang and their UC Davis colleagues note that if their therapy is successful, it will also have an economic benefit for California and beyond. Because spina bifida is a lifelong condition, it has an enormous financial impact on families.

“Spina bifida is a devastating condition for babies born with this disorder and the families who care for them,” said Maria T. Millan, president and chief executive officer of CIRM. “CIRM has funded this important work from its earliest stages and we are committed to working with Dr. Farmer’s team to moving this work to the stage where it can be tested in patients.”

Learn more about Spina Bifida

-

- My Son’s First Surgery for Spina Bifida

- Everett’s Update: Flourishing After Fetoscopic Surgery

- What a Difference a Year Can Make

- Watch a video of Dr Farmer discussing her team’s research.