Mother Stephanie Milner tells the story of her family’s experience with a Twin Anemia Polycythemia Sequence (TAPS) diagnosis.

To this day, I’ll never, ever forget the moment that they told us we were expecting twins. While looking at the ultrasound screen, the tech said, “Here’s a baby, and here’s the other one! Congratulations!”

It was probably the only time in my life I’ve ever been entirely speechless. The whole morning turned into changing and canceling appointments, meeting new doctors, and understanding a real new world of twins. My new doctor explained so many things about my pregnancy, including how it had become high risk, and that we needed screening every two weeks for things like TTTS. “But don’t worry!” he said. “It only happens to 15% of this type of pregnancy. You won’t be one of them.”

In the meantime, I was still processing the word “twins.” It wouldn’t be until much later that I would realize that these words were a little ominous.

Routine Checks are Vital for TAPS

Every two weeks, like clockwork, my appointments came. I was hideously sick from morning sickness and lost a considerable amount of weight, but my pregnancy progressed pretty normally. Everything was fine up until 24 weeks.

On this day, I went to my routine appointment. A few days earlier, I’d been feeling that I had a constant backache and that my belly was getting pretty tight, but I hadn’t thought that much about it. It wasn’t all that inconvenient; it honestly just felt like my skin was too tight on my stomach. Nothing to worry about, right?

It turns out it was. At that appointment, I found out that my donor twin had just 1 centimeter of fluid, and my recipient twin had an incredible 10.5 centimeters. My local team suspected I had Twin to Twin Transfusion Syndrome (TTTS) and rushed me to the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC) here in the Netherlands. It was confirmed I had stage 1 TTTS, and we chose to manage it conservatively through expectant management, with the understanding that if anything changed, we would undergo laser surgery.

They also were concerned by another thing – our babies were showing that their brain dopplers (MCA Dopplers) had started to move apart, and the donor twin was anemic.

It honestly seemed like time stopped moving. We were at the hospital every two days getting checked, and while our fluid levels dropped out of the danger zone, our MCA dopplers progressively got worse.

We had developed spontaneous TAPS.

What is TAPS?

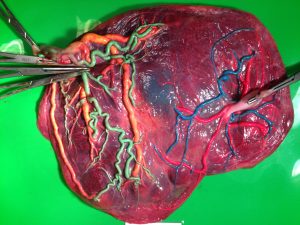

TAPS is Twin Anemia Polycythemia Sequence, where small connections in the placenta pass red blood cells from donor to recipient. Unlike TTTS, where the vessels are large, and the change is rapid, TAPS is caused by tiny connections, less than one millimeter thick. The blood flows between the babies at a rate of around 5 to 15 milliliters a day (less than an espresso). Where TTTS happens quickly, TAPS occurs much more slowly and over a more extended period.

TAPS Placenta

There are two forms of TAPS – the more common form is post-laser TAPS, which happens in around 16% of post-TTTS laser surgery cases, and spontaneous TAPS, which is rarer – only happening in about 3-5% of monochorionic twin pregnancies.

Between 24-30 weeks, things remained stable. We still were being monitored, our MCA dopplers were moving apart, but the babies continued to grow and develop and showed no issues. It was stressful, naturally, and we felt relieved at every appointment to know that things were not changing in the wrong direction.

That is, until our appointment at 31 weeks. What I thought was going to be yet another routine appointment wasn’t.

Diagnosis to Delivery

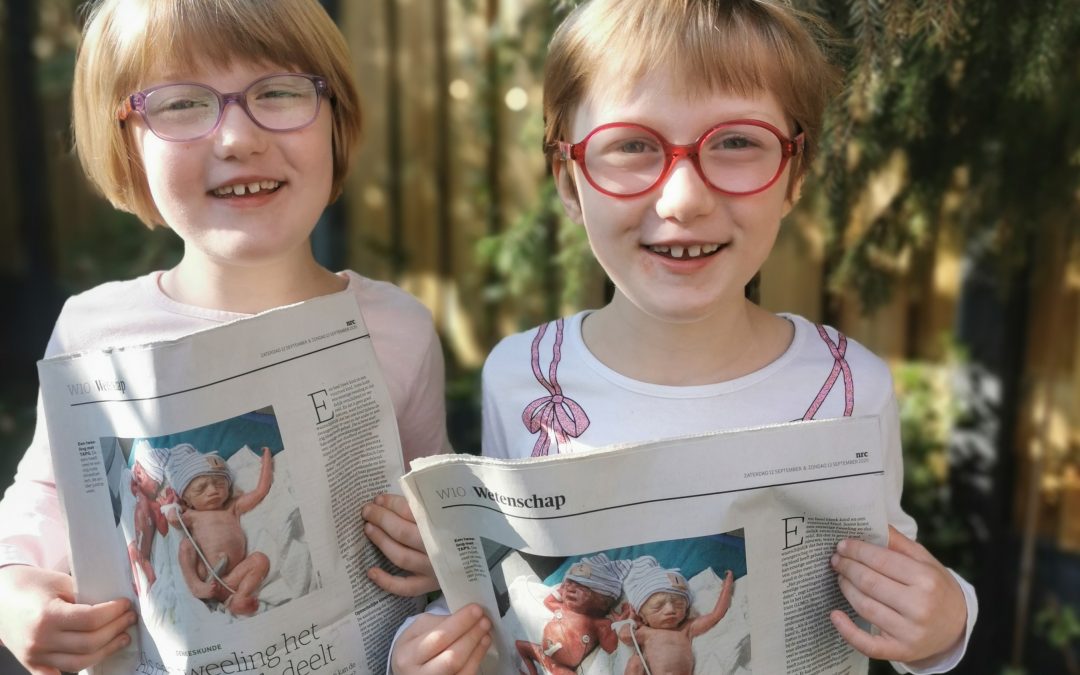

At this appointment, I knew that something was wrong when the ultrasound technician went silent and then went to get his colleague. It was confirmed that they found a shadow on the brain of my recipient twin and that it could be a bleed, so the decision was made to deliver my girls. Two days later, my girls arrived into the world on a cold December morning, where it was confirmed that they were indeed stage 3 TAPS.

The author’s twin daughters at birth.

My donor twin ended up with three blood transfusions, and my recipient had two partial blood exchanges. They said that my donor’s blood was the consistency of rose wine, and my recipient’s like ketchup – which is pretty typical for TAPS twins.

Thankfully, I was under the care of the LUMC team who research TAPS. My girls ended up spending five weeks (recipient) and six weeks (donor) in the NICU, and they will be turning seven this year.

I put it all down to the dumb luck that I was referred to the LUMC – and their care and research saved the lives of my babies.

Why you need to worry about TAPS

Right now, the biggest problem is that TAPS remains under-diagnosed. There is no current “best treatment,” but treatment options do exist. However, because there’s no consensus on treating TAPS, many guidelines don’t recommend routine MCA dopplers.

You need to be getting MCA dopplers every two weeks, starting between 16 and 20 weeks. They should plot these and watch for them moving apart, as the wider the distance, the more chance there is of developing TAPS. After birth, if they suspect that your babies developed TAPS in utero, you should insist that their hemoglobin and reticulocytes are checked in blood tests. You can find out more about diagnosing TAPS on the TAPS Support website.

Why it’s so important to diagnose TAPS in utero is the long term effects, especially in spontaneous TAPS. In a recent study, 44% of TAPS donors had some degree of neurodevelopmental impairment, and 15% of donors had a form of deafness called Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder.

Unfortunately, in some cases, TAPS can also be fatal. Screening is crucial.

And a final note…

My passion for TAPS advocacy comes from a straightforward thing. My daughters, Emilie and Mathilde, are the faces of TAPS. The photo is taken on the 12th of December 2013, when they were born. Their picture is seen worldwide and raises awareness of TAPS research and the fact that TAPS is a genuine threat to monochorionic twin pregnancies. We don’t know the best treatment, but with more research, we will know more. The TAPS Support Foundation is dedicated to raising awareness of TAPS and promoting TAPS research, and we’re proud to stand beside the Fetal Health Foundation to do so. TAPS is real and can be treated with successful outcomes.

TAPS Resources:

The TAPS Support Foundation and TAPS Support

- Dispelling Myths about Antenatal TAPS: A Call for Action for Routine MCA-PSV Doppler Screening in the United States – L Nicholas et al

- Twin Anemia Polycythemia Sequence: Current Views on Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Criteria, Perinatal Management, and Outcome – LSA Tollenaar et al

- Treatment and outcome of 370 cases with spontaneous or post‐laser twin anemia–polycythemia sequence managed in 17 fetal therapy centers – LSA Tollenaar et al

- Improved prediction of twin anemia–polycythemia sequence by delta middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity: new antenatal classification system – LSA Tollenaar et al

- High risk of long‐term neurodevelopmental impairment in donor twins with spontaneous twin anemia–polycythemia sequence – LSA Tollenaar et al

- The TAPS Trial

- Twin anemia-polycythemia sequence in two monochorionic twin pairs without oligo-polyhydramnios sequence – E Lopriore et al

- Solomon Technique Versus Selective Coagulation for Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome – F Slaghekke et al.