Ella’s life is saved after surgery for sacrococcygeal teratoma at the Colorado Fetal Care Center

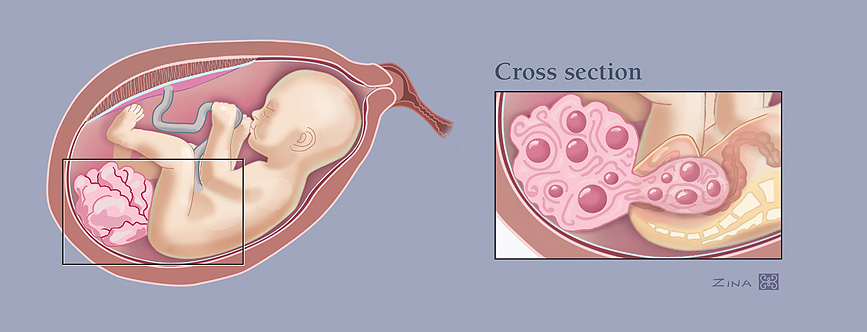

Sacrococcygeal teratomas are tumors that appear in the lower back and buttocks of the fetus. They are most often at the base of the tailbone (coccyx), and can be located inside or outside the pelvis.

Small- or medium-sized tumors without excessive blood flow will not cause problems for the fetus. If the tumor is made up of mostly solid tissue and has a lot of blood flow, the fetus’ heart has to pump to circulate blood both to its body and to the tumor. In severe cases, the tumor can grow so large that the fetus’ heart can’t keep up, putting the fetus at risk of heart failure. This condition is known as hydrops.

Diagnosis

Sacrococcygeal teratomas are usually discovered because a blood test performed on the mother at 16-weeks gestation shows a high amount of a protein called alpha fetoprotein. Within two weeks following the initial diagnosis, these tests are recommended:

- Ultrasound to analyze the blood supply, size and characteristics of the tumor

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the fetus to obtain detailed views of the tumor, the spine and the surrounding structures in the pelvis

- A fetal echocardiogram to assess how hard the heart is working

Fetuses with large, mostly solid tumors need to be monitored frequently between 18- and 28-weeks’ gestation to evaluate tumor growth and the potential for hydrops.

Treatment

All sacrococcygeal teratomas require complete surgical resection before or after birth.

If hydrops develops before 32-weeks’ gestation, the fetus usually will not survive without immediate intervention before birth. Fetal interventions range from a needle-based approach to open fetal surgery, where the mother and fetus undergo an operation to remove or reduce the size of the tumor.

If hydrops does not develop but the tumor is very large, a cesarean-section delivery and extensive operation after birth may be necessary.

If hydrops is not present or the tumor is not too large, surgery can occur after birth. Small tumors will be removed along with the coccyx bone. More complex surgery is required for tumors that affect the baby’s abdomen.

Although these tumors can grow very large, they usually are not malignant. If the tumor is malignant and has not spread, surgery alone is adequate therapy. Tumors that have spread tend to respond well to surgery and chemotherapy.

Outcomes

Most babies do well once the tumor is completely removed. They should be evaluated, however, by a pediatric oncologist and pediatric surgeon throughout childhood, as there can be future consequences such as tumor recurrence or difficulty with bowel and/or bladder control.

*Information provided by UC Davis Fetal Care and Treatment Center

TREATMENT CENTERS

Filter List: